Georgia judge to toss landmark racketeering charges against 'Cop City' protesters

A Georgia judge says he's going to dismiss racketeering charges against all 61 defendants accused of trying to stop the construction of a police and firefighter training facility known as “Cop City."

FILE - Andrew Douglas, of Atlanta, raises his fist during a protest over plans to build a police training center, March 9, 2023, in Atlanta. (AP Photo/Alex Slitz, file)

ATLANTA (AP) — A Georgia judge on Tuesday said he will toss the racketeering charges against all 61 defendants accused of a yearslong conspiracy to halt the construction of a police and firefighter training facility that critics pejoratively call “Cop City.”

Fulton County Judge Kevin Farmer said he does not believe Republican Attorney General Chris Carr had the authority to secure the 2023 indictments under Georgia’s Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations law, or RICO. Experts believe it was the largest criminal racketeering case ever filed against protesters in U.S. history.

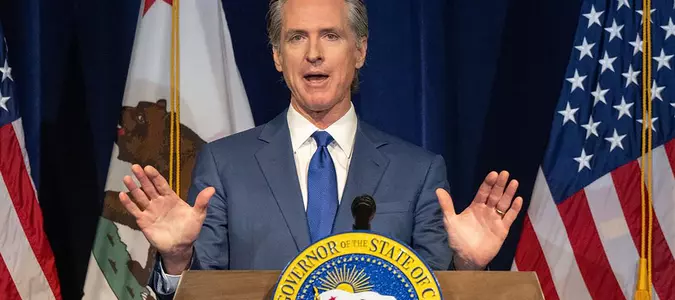

Farmer said during a hearing that Carr needed Gov. Brian Kemp 's permission to pursue the case instead of the local district attorney. Prosecutors earlier conceded to the judge that they did not obtain any such order.

“It would have been real easy to just ask the governor, ‘Let me do this, give me a letter,’” Farmer said. “The steps just weren't followed.”

Five of the 61 defendants were also indicted on charges of domestic terrorism and first-degree arson. Farmer said Carr also didn't have the authority to pursue the arson charge, though he believes the domestic terrorism charge can stand.

Farmer said he plans to file a formal order soon and is not sure whether he would quash the entire indictment or let the domestic terrorism charge stand, though he said he expects the prosecution to appeal regardless.

Deputy Attorney General John Fowler told Farmer that he believes the judge's decision is “wholly incorrect.”

The long-brewing controversy over the training center erupted in January 2023 after state troopers who were part of a sweep of the South River Forest that killed an activist who authorities said had fired at them. Numerous protests ensued, with masked vandals sometimes attacking police vehicles and construction equipment to stall the project and intimidate contractors into backing out.

The defendants faced a wide variety of allegations — everything from throwing Molotov cocktails at police officers, to supplying food to protesters who were camped in the woods and passing out fliers against a state trooper who had fatally shot the protester known as “Tortuguita.” Each defendant faced up to 20 years in prison on the RICO charge.

Carr, who is running for governor, had pursued the case, with Kemp hailing it as an important step to combat "out-of-state radicals that threaten the safety of our citizens and law enforcement.”

But critics had decried the indictment as a politically motivated, heavy-handed attempt to quash the movement.

Emerging in the wake of the 2020 racial justice protests, the “Stop Cop City” movement gained nationwide recognition as it united anarchists, environmental activists and anti-police protesters against the sprawling training center, which was being built in a wooded area that was ultimately razed in DeKalb County.

Activists argued that uprooting acres of trees for the facility would exacerbate environmental damage in a flood-prone, majority-Black area while serving as an expensive staging ground for militarized officers to be trained in quelling social movements.

The training center, a priority of Atlanta Mayor Andre Dickens, opened earlier this year, despite years of protests and millions in cost overruns, some of which was due to the damage protesters caused, and police officials’ needs to bolster 24/7 security around the facility.

But over the past two years, the case had been bogged down in procedural issues, with none of the defendants going to trial. Farmer and the case’s previous judge, Fulton County Judge Kimberly Esmond Adams, had earlier been critical of prosecutors’ approach to the case, with Adams saying the prosecution had committed “gross negligence” by allowing privileged attorney-client emails to be included among a giant cache of evidence that was shared between investigators and dozens of defense attorneys.

Prosecutors had repeatedly apologized for the delays and missteps, but lamented the difficulty of handling such a sprawling case, though Farmer pointed out that it was prosecutors who decided to bring this “61-person elephant” to court in the first place.